How Charlie Ledley and Jamie Mai turned $110,000 into almost $130 million

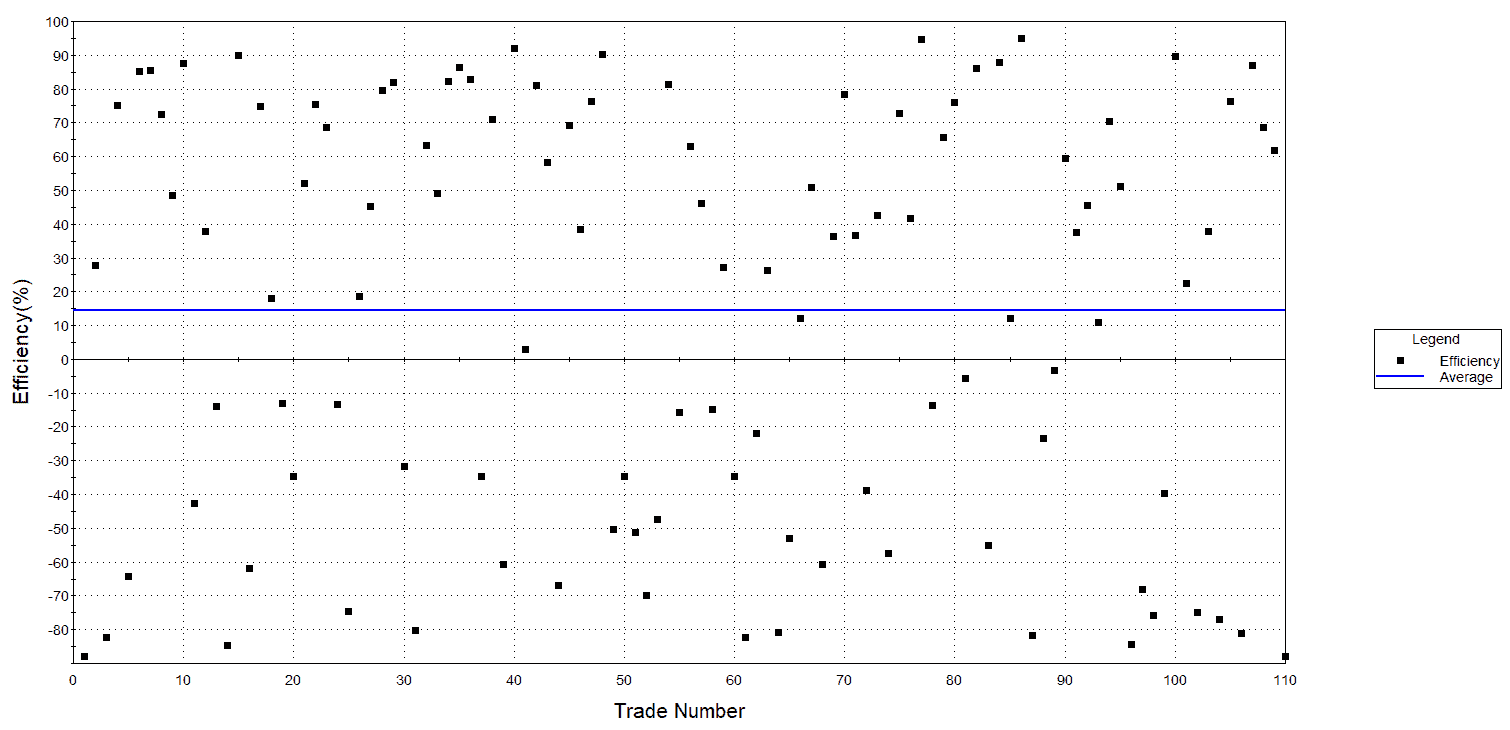

In 2003, Charlie Ledley and Jamie Mai, at the tender age of 30 formed Cornwall Capital Management (the firm has produced an average annual compounded net return of 40% – 52% gross), opening a Charles Schwab account with an initial investment of $110,000. Neither of them was an experienced trader by the time they began their endeavor. Their only experience came from brief stints working in private equity. Which formed their view that public markets are less efficient compared to private markets and that investors in public markets often miss the bigger picture. Their trading strategy was born, go against the crowd and find market inefficiencies.

With their view they first hit it big with an investment in a credit card company called Capital One Financial, they studied the business, reports and interviewed all sorts of people including company VP. Then they decided to buy two-year LEAPS at $40 with $3 (stock price was $30 by that time) they invested $26,000 representing 23.6% of their total portfolio. When they came across their investment the stock tanked 60% in just two days over accusations of fraud among the company’s directors. However, the company’s financial performance seemed stellar and nothing had yet materialized from the SEC’s investigation. Charlie and Jamie did their own research and decided that either the company was vastly undervalued, or the company was worthless because it was run by crooks. Their final assumption was that the company was not run by crooks and so they bought long term call options. As Capital One Financial was vindicated by the SEC its share price inflected up to pre-crisis levels and Cornwall Capital’s option position ballooned in value going from $26,000 to $526,000.

Charlie and Mai made use of the strong disconnect between the mathematical models and the valuation made by rational investors. And so, rather than buy the Capital One stock for a 75% return, Charlie and Mai bought wrongly priced option contracts instead which earned them a staggering return of 2000%.

Their second big hit was their investment in distressed company United Pan European Cable where they bought $500,000 long term call options. When UPC rallied their investment of $500,000 turned into $5.5 million. Their third investment on a company that delivered oxygen tanks directly to sick people in their homes went from $20,000 to $3,000,000.

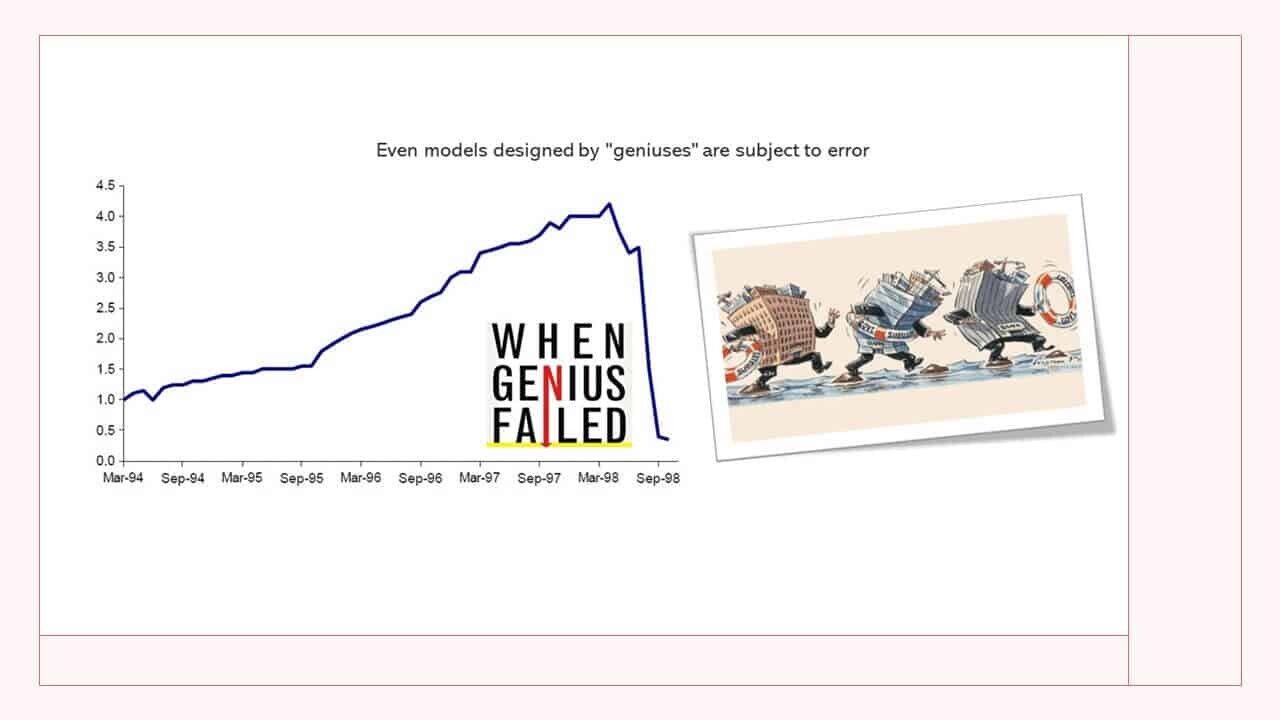

When placing these bets, they spent a lot of time building Black-Scholes models calculating what happens when you change various assumptions in them. What struck them the most was how easily one could identify situations where the market mispriced potential outcomes, situations that were likely to end in one of two dramatic ways. They both realized that way to often markets were too certain about inherently uncertain things.

Each time they came upon a tantalizing long shot, one of them set to work on making the case for it, in an elaborate presentation with PowerPoint slides. They only created these presentations to hear how plausible they sounded when they pitched their ideas to each other.

They sought asymmetrical returns: risk 1 to make 10, 20, 100 or even more.

Where can opportunities of asymmetrical returns be found?

“where a price dislocation has occurred, either at a single company or across an industry, because the market has identified a particular idiosyncratic risk and assigned an uncertainty discount to it.”

“It’s easy to frame the questions in special situations because the market has already identified the problem and applied the discount. Although markets are generally good at estimating the magnitude of a contingent liability, they are often poor at evaluating outcomes probabilistically. Examples include litigations, regulatory actions, or other events that create the perception of going concern risk.”

How they did their research?

“We did background checks on management. We spoke to people who had gone to college with the CEO because the essential question related to the ethical character of management”

How did they structure their bets?

Example:

“After the financial crisis, however, the Australian dollar and Swiss franc exhibited extreme inverse correlation because of the risk-on/risk-off psychology if the Swiss franc was up sharply, you could be relatively sure that the Australian dollar would be down sharply and vice versa.

We were looking for an efficient way of getting short the euro. Implied volatility on the euro puts was expensive.

We cheapened the premium substantially by taking our exposure through a worst of option: an exotic option that is priced based on a correlation input in addition to the standard inputs for a vanilla option.

You pay a single premium for a basket of options. Worst of option structures are cheaper because the payout is determined by whichever option performs more poorly from the buyer’s perspective. As long as one of the options expires out-of-the-money, the option buyer will lose the entire premium.

The worst option we purchased was very cheap because a strong negative correlation had emerged between EUR/AUD versus EUR/ CHF;

using plain vanilla puts in the EUR/AUD or EUR/CHF crosses, we would have had to pay a premium of about 4.5% of notional. We could do the worst of basket trade for less than one-tenth that amount.

Interviewer: the market was pricing the premium at a level that assumed that the current correlation was the most likely future correlation without taking into account that there was a potential event — a debt fear induced selloff in the euro — that could radically alter the existing correlation.

Yes, and if the correlation was −0.60, the dealers would sell us the option priced at a correlation assumption of −0.50 and high-five each other because they had just ripped our faces off…

The euro did break down against both the Australian dollar and Swiss franc in mid-2009, and we ended up netting over six times our invested capital on the trade.“

Where did they make the biggest profits? – the big short

“Since we did not have the domain expertise necessary to do bottom-up fundamental analysis in the MBS space, we hired a highly regarded research analyst who had recently left BlackRock to create his own hedge fund. He was able to evaluate the quality of the collateral underlying all the MBS issuances we were interested in analyzing based on such metrics as loan-to-values, FICO scores, and seasoning of nonperforming loans. He then came up with a list of the worst ABS issuances, based on his fundamental analysis. We then went out and looked for CDOs that had the most overlap with his list. We were pleasantly surprised to find CDOs that had a large overlap.”

“It wasn’t until much later that we realized that the security-selection acumen we thought we’d demonstrated in picking some of the worst performing CDOs was in fact a reflection of much deeper work that had been done by other investors, such as Michael Burry of Scion Capital, who knew the market much better than we did. It turned out that the reason we were able to find CDOs whose collateral happened to be the absolute worst-performing subprime MBS was because Burry had gone to dealers months earlier and convinced them to create synthetic securitizations for the specific names he wanted to buy protection on [i.e., short].”

“By arriving relatively late at the scene toward the end of 2006, we unwittingly put ourselves in a position to reap even greater rewards from the dealers’ avarice. In selling CDS to guys like Burry, they were synthetically replicating the bonds he wanted to short. It didn’t take long for credit derivative dealers to have the thought that if synthetic MBS made sense, then so did synthetic CDOs“

Where to go from here:

Recommended reading – price efficiency and short selling, short selling and over optimism, Activist Investors, Distressed Companies, and Value Uncertainty, Option Volatility and Pricing, Equity Derivatives: Volatility and Correlation, Analysis, Geometry, and Modeling in Finance: Advanced Methods in Option Pricing

Useful tools: Options Trading and Portfolio Investment Analysis and Design Tools by Peter Hoadley