What We Can Learn From The Long Term Capital Management Hedge Fund Collapse

In this article we are going to talk about financial market history and why it is important for both the fundamental investor and quantitative trader to know how these events unfolded and what impact they had on the market. We put our focus on the LTCM hedge fund collapse and the lessons you can learn from it.

Algorithmic trading is an extremely sophisticated area of quantitative finance. It can take a lot of time to gain the necessary knowledge to develop an algorithmic trading strategy on your own. In our opinion it not only requires programming expertise but a knowledge about the history of the markets as well.

A quant traders tool kit should therefore consist of the following major components:

- Programming skills

- Probability & Statistics

- Knowledge about financial market history (manage volatility & risks, generate ideas)

The last aspect is hugely overlooked by most market practitioners. Nevertheless, it is absolutely crucial to read as much as possible about financial market history. There is a reason why the whole field of quantitative financial history has really exploded in the past couple of years. After a lot of trial and error we discovered that by carefully studying events of the past we can improve our overall trading results and come up with new ideas we haven’t thought about before.

The Long Term Capital Management fiasco is full of lessons about the following:

- Strategy risk

- Model errors

- Importance of risk management

- Breakdown of historical correlations

- Dangers of too much leverage

- Ignoring financial market history

Long-Term Capital Partners was founded in 1993 by John Meriwether, who previously worked as the head of fixed income trading at Salomon Brothers. Even after being forced to leave Salomon in 1991 due to the firm’s treasury auction rigging scandal (another marker buoy), Meriwether maintained huge loyalty from a team of highly respected relative-value fixed income traders. Meriwether and LTCM had more credibility than the average broker/dealer on Wall Street when they teamed up with a handful of these traders, two Nobel laureates, Robert Merton and Myron Scholes, and former regulator David Mullins.

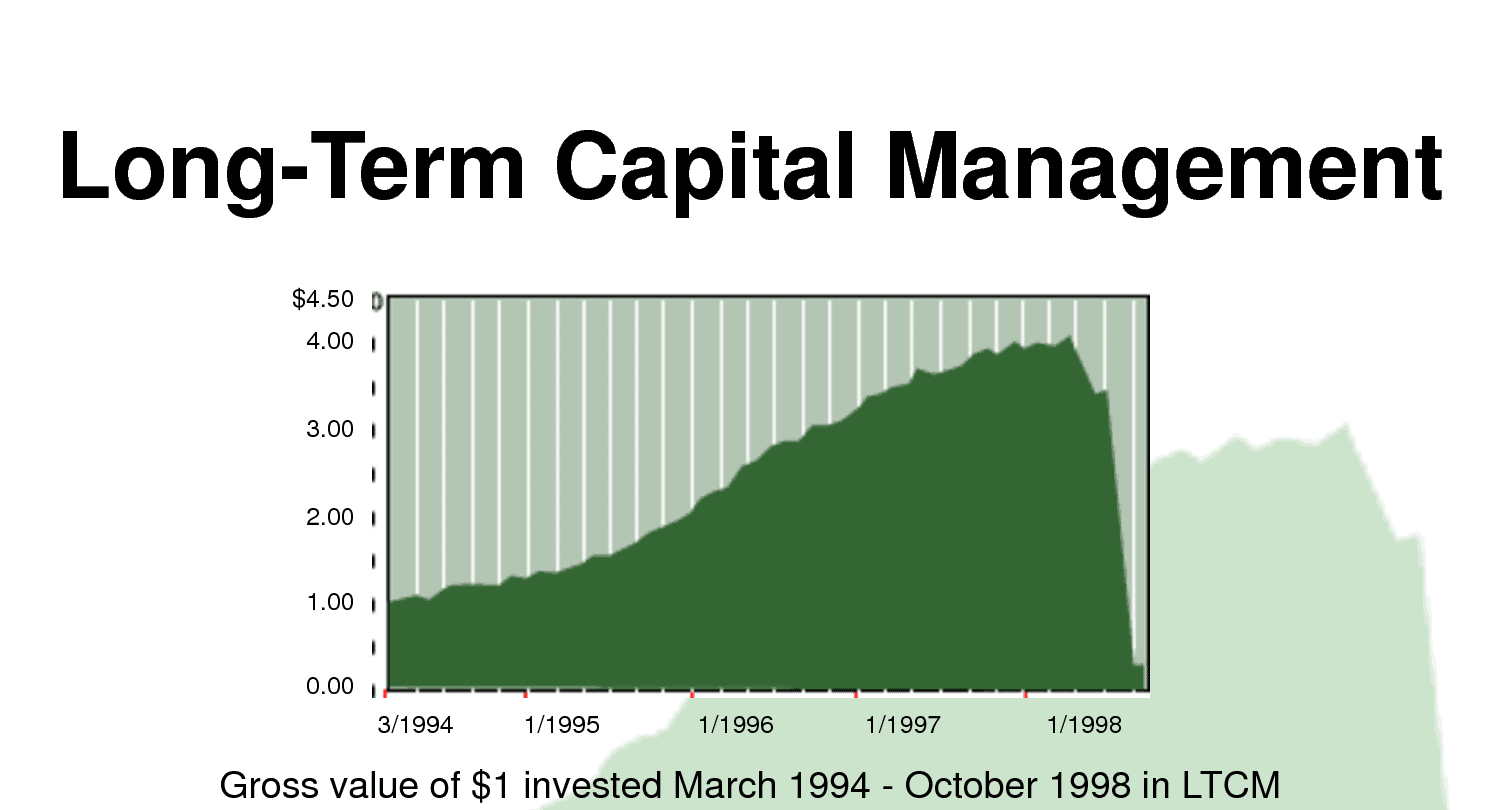

It was a game in the sense that LTCM was unregulated, free to operate in any market, had no capital charges, and only minimal reporting obligations to the SEC. It traded on its good name with a slew of respectable counterparties as if they were all members of the same club. That meant being able to put on interest rate swaps at market rates with no initial margin – a critical component of its strategy. It meant being able to borrow 100 percent of the value of any top-tier collateral and then use that cash to buy more securities and use them as collateral for additional borrowing: in theory, it could leverage itself indefinitely. In its first two years of operation, LTCM generated a 43 percent and a 41 percent return, respectively, and amassed a whopping $7 billion of capital.

Meriwether was a well-known relative-value trader. Relative value implies (in theory) little outright market risk because a long position in one instrument is offset by a short position in a similar instrument or its derivative. It entails betting on minor price differences that are likely to converge over time as the arbitrage is discovered and eroded by the rest of the market. Typical early LTCM trades included buying Italian government bonds and selling German Bund futures; buying theoretically underpriced off-the-run US treasury bonds (due to their lower liquidity) and selling on-the-run (more liquid) treasuries. It used the same arbitrage strategy in the interest-rate swap market, betting that the spread between swap rates and the most liquid treasuries would narrow. It used old-school callable Bunds against Deutsche Mark swaptions. It was a major player on the world’s futures exchanges, trading not only debt but also equity products. Certainly, leverage was required to achieve a 40% return on capital. In theory, increasing volume does not increase market risk, as long as you stick to liquid instruments and don’t become so large that you become the market.

Some of the larger macro hedge funds had run into this issue and reduced their size by returning money to investors. When LTCM returned $2.7 billion to investors in the fourth quarter of 1997, it was assumed to be for the same reason: a prudent reduction in its positions relative to the market.

However, it appears that the positions were not reduced in proportion to the capital reduction, so the leverage increased. In addition, new risks had been introduced into the mix. LTCM exploited the credit spread between mortgage-backed securities (including Danish mortgages) and government bond markets. The company then ventured into equity trading. In 1997, it sold equity index options at a high premium. According to press reports, LTCM took speculative positions in takeover stocks.

According to a SEC filing dated June 30, 1998, LTCM had $541 million in equity stakes in 77 different companies. It also made inroads into emerging markets such as Russia. According to one report, Russia was “8 percent of its book,” which equates to $10 billion!

Investment banks, some of LTCM’s main competitors, had been clamoring to invest in the fund. Meriwether used a formula that attracted new investment while also giving him and his partners a virtual put option on the fund’s performance. Under this formula, UBS put in $800 million in the form of a loan and $266 million in straight equity in 1997. Credit Suisse Financial Products contributed a loan of $100 million and $33 million in equity. Other loans may have been secured in this manner, but they have not been disclosed. Investors in LTCM agreed to keep their money in the fund for at least two years. LTCM entered 1998 with $4.8 billion AUM.

According to a New York Sunday Times article, the big trouble for LTCM began on July 17, when Salomon Smith Barney announced it was liquidating its dollar interest arbitrage positions: “For the rest of that month, the fund dropped about 10% because Salomon Brothers was selling everything that Long-Term owned.” (The article was written by Michael Lewis, a former Salomon bond trader and Liar’s Poker author. Lewis returned to his former colleagues at LTCM following the crisis and describes some of the trades on the firm’s books).

Russia declared a moratorium on its ruble and domestic dollar debts on August 17, 1998. Hot money, already jittery as a result of the Asian crisis, fled to high-quality assets. The most liquid US and G-10 government bonds were the most preferred. Spreads between on-the-run and off-the-run US treasuries widened as well.

The majority of LTCM’s bets had been variations on the same theme, namely the convergence of liquid treasuries and more complex instruments that demanded a credit or liquidity premium. Unfortunately, the convergence became a dramatic divergence.

Counterparties to LTCM, who mark their LTCM exposure to market at least once a day, began to request more collateral to cover the divergence. According to Lewis, the LTCM portfolio lost $550 million in a single day on August 21. Meriwether and his team, still convinced of the logic of their trades, believed that all they needed was more capital to get through the distorted market.

Maybe they were correct. However, there were several factors working against LTCM. Who could forecast the time span over which rates would converge? Counterparties had lost faith in themselves and in LTCM. Many counterparties, some of whom were LTCM disciples, had entered into the same arbitrage trades. To meet margin calls, LTCM was forced to liquidate.

Meriwether informed his investors in a letter dated September 2, 1998, that the fund had lost $2.5 billion, or 52 percent of its value that year, including $2.1 billion in August alone. The company’s capital base had shrunk to $2.3 billion. Meriwether was looking for an additional $1.5 billion in investment to see the fund through. He approached those known to have such investible capital, such as George Soros, Julian Robertson, and Warren Buffett, chairman of Berkshire Hathaway and previously an investor in Salomon Brothers (LTCM, incidentally, had a $14 million equity stake in Berkshire Hathaway), as well as Jon Corzine, then co-chairman and co-chief executive officer at Goldman Sachs. Goldman Sachs and JP Morgan were also tasked with searching the market for capital.

However, no new capital was forthcoming. Perhaps these large investors were waiting for the price of an equity stake in LTCM to fall even further. Or they were profiting by trading against LTCM’s positions. If true, it would have been difficult and risky for LTCM to show potential buyers more details about its portfolio under these conditions. According to a later Financial Times report, two Merrill executives paid a visit to LTCM headquarters on September 9, 1998, for a “due diligence meeting” (on October 30, 1998). They were given “general information about the fund’s portfolio, strategies, losses to date, and intent to reduce risk.” However, according to Merrill, LTCM did not disclose its trading positions, books, or any other documents.

Concerns about LTCM were raised by the US Federal Reserve system, particularly the New York Fed, which is closest to Wall Street. Bear Stearns, LTCM’s clearing agent, said in the third week of September that it needed another $500 million in collateral to continue clearing LTCM’s trades. Bill McDonough, chairman of the New York Fed, made “a series of calls to senior Wall Street officials to discuss overall market conditions” on Friday, September 18, 1998, he told the House Committee on Banking and Financial Services on October 1. “Everyone I spoke with that day expressed concern about the serious impact a deteriorating Long-Term situation could have on global markets.“

The New York Fed’s executive vice president, Peter Fisher, decided to look into the LTCM portfolio. On September 20, 1998, he and two Fed colleagues, assistant treasury secretary Gary Gensler and Goldman and JP Morgan bankers, paid a visit to LTCM’s offices in Greenwich, Connecticut. They were all taken aback by what they saw. Although LTCM’s major counterparties had closely monitored their bilateral positions, it was clear that they had no idea of LTCM’s total off balance sheet leverage. LTCM had swapped with 36 different counterparties. In many cases, it had put on a new swap to reverse a position rather than unwinding the first swap, which would have necessitated a mark-to-market cash payment in either direction. LTCM’s on-balance-sheet assets were approximately $125 billion, with a capital base of $4 billion and a leverage of approximately 30 times. However, LTCM’s off-balance-sheet business, with a notional principal of around $1 trillion, multiplied that leverage tenfold.

Off-balance-sheet contracts were mostly nettable through bilateral Isda (International Swaps and Derivatives Association) master agreements. The vast majority of them were also collateralized. Unfortunately, the collateral’s value had plummeted since August 17.

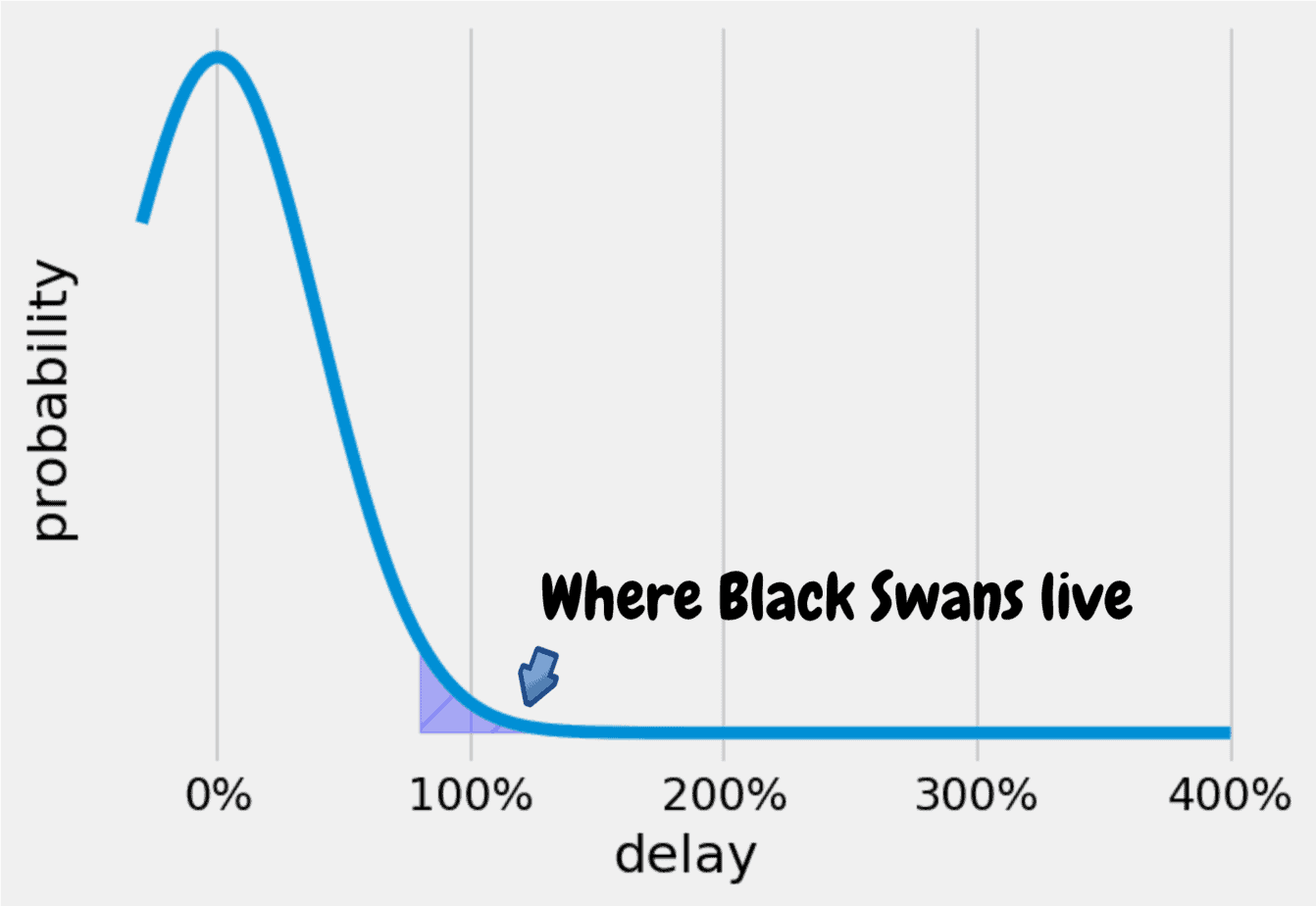

With two of the original masters of derivatives and option valuation among its partners, LTCM had to have put its portfolio through stress tests to match the recent market turmoil. However, as with many other value-at-risk (Var) modelers on the street, their worst-case scenarios had been outplayed by the market’s horribly correlated behavior since August 17. Such a flight to quality had not been predicted, owing to its obvious irrationality.

Stress Tests

According to LTCM executives, their stress tests included examining the 12 largest deals with each of their top 20 counterparties. This resulted in a maximum loss of around $3 billion. However, on that Sunday evening, it appeared that the mark-to-market loss, based solely on those 240 or so transactions, could exceed $5 billion. And that was without taking into account all of the other trades, some of which were in highly speculative and illiquid instruments.

The following day, Monday, September 21, 1998, bankers from Merrill Lynch, Goldman Sachs, and JP Morgan continued to investigate the problem. It was still hoped that the portfolio could be sold to a single buyer – the simplest solution.

According to Lewis’ article, LTCM’s portfolio suffered its second-largest loss of $500 million that day. Lewis claims that half of that was lost on a short position in five-year equity options. Lewis documents brokers’ belief that AIG intervened in thin markets to drive up option prices in order to profit from LTCM’s weakness. AIG was part of a consortium negotiating to buy LTCM’s portfolio at the time, as it was later revealed. By this point, LTCM’s capital base had shrunk to $600 million. That evening, UBS sent a team to Greenwich to study the portfolio due to its particular exposure on a $800 million credit, with $266 million invested as a hedge.

The Fed’s Peter Fischer invited those three banks and UBS to breakfast the next day at the Fed’s Liberty Street headquarters. Given the lack of a single buyer, the bankers decided to form working groups to investigate possible market solutions to the problem. Proposals included purchasing LTCM’s fixed income positions as well as “lifting” the equity positions (which were a mixture of index spread trades and total return swaps, and the takeover bets). During the day, a third option emerged as the most promising: seeking portfolio recapitalization from a consortium of creditors. However, any action had to be taken as soon as possible.

The risk was that LTCM’s single default would trigger cross-default clauses in its master agreements, resulting in a mass close-out in the over-the-counter derivatives markets. Banks that close their positions with LTCM must rebalance any hedges they may have on the other side. The market would quickly become aware of their need to rebalance and would begin to move against them. In a vicious circle, mark-to-market values would fall.

LTCM appears to have sold short up to 30% of the volatility of the entire underlying market in the case of the French equity index, the CAC 40. The Banque de France was concerned that a quick close-out would have a negative impact on French equities. There was a broader concern that an unknown number of market participants had convergence positions similar to or identical to LTCM’s. In such a one-way market, there may be a mad dash for the exit. The possibility of a meltdown in developed markets on top of the panic in emerging markets seemed real. Bear Stearns, LTCM’s clearing agent, threatened to foreclose the next day unless it received $500 million more collateral. Until now, LTCM had resisted the temptation to use a $900 million standby facility syndicated by Chase Manhattan Bank because it knew doing so would frighten its counterparties. But the situation had deteriorated to the point of no return. LTCM requested $500 million from Chase. It only received $470 million because two syndicate members refused to contribute. To advance the consortium plan, the largest banks, either LTCM’s creditors or major players in the over-the-counter markets, were summoned to a meeting at the Fed that evening. The plan was for each of them to contribute $250 million to recapitalize LTCM for $4 billion.

At 7 p.m., the four core banks met to review a term sheet prepared by Merrill Lynch. Then, at 8.30 a.m., bankers from nine additional institutions arrived. Bankers Trust, Barclays, Bear Stearns, Chase, Credit Suisse First Boston, Deutsche Bank, Lehman Brothers, Morgan Stanley, Credit Agricole, Banque Paribas, Salomon Smith Barney, and Société Générale were among the firms they represented. David Pflug, Chase’s head of global credit risk, warned that nothing would be gained a) by rehashing the mistakes that had led them to this point, and b) by arguing about who had the most exposure: they were all in this together and equally.

The delicate question was how to preserve value in the LTCM portfolio, given that the banks in the room would be equity investors while also looking to liquidate their own positions with LTCM to maximize advantage. It was obvious that John Meriwether and his partners would have to be involved in order to keep such a complex portfolio running. But what incentive would they have if they were no longer interested in profits? Chase insisted that any bailout must first repay the $470 million borrowed from the syndicated standby facility. However, nothing could be finalized that night because few of the representatives present could commit to pledging $250 million or more of their company’s funds.

The meeting resumed the following morning at 9.30 a.m. Warren Buffett, a client of Goldman Sachs, offered to buy the LTCM portfolio for $250 million and recapitalize it with $3 billion from his Berkshire Hathaway group, $700 million from AIG, and $300 million from Goldman. Meriwether and his team would have no management responsibilities. LTCM’s existing liabilities would not be assumed, but all current financing would have to be maintained. Meriwether had until 12.30 p.m. to make a decision.

By 1pm, it was clear that Meriwether had rejected the offer, either because he didn’t like it or, according to his lawyers, because he couldn’t do so without consulting his investors, which would have put him late.

The bankers were taken aback by Goldman’s dual role. Despite frequent requests for information about other potential bidders, Goldman had given no indication that something was in the works at previous meetings. The banks had returned to the consortium solution. Because there were only 13 banks, rather than 16, each would have to contribute more than $250 million. Bear Stearns made no offer, believing that its role as LTCM’s clearing agent was sufficiently risky. Their special relationship may have been the source of some friction – LTCM had a $18 million equity stake in Bear Stearns, which was matched by $10 million investments in LTCM by Bear Stearns principals James Cayne and Warren Spector. Lehman Brothers declined to participate as well. In the end, 11 banks contributed $300 million each, Société Générale $125 million, and Credit Agricole and Paribas each $100 million, for a total of $3.625 billion in new equity. Meriwether and his team would keep a 10% stake in the company. They would manage the portfolio under the supervision of an oversight committee comprised of members of the new shareholding consortium.

The message to the market was that there would be no asset fire-sale. The LTCM portfolio would be run as a business.

According to press reports, LTCM continued to lose value in the first two weeks following the bailout, particularly on its dollar/yen trades, with a loss of around $200 million. More attempts were made to sell the portfolio to a single buyer. According to press reports, the new LTCM shareholders met with Buffett and Saudi prince Alwaleed bin Abdelaziz. However, there was no sale. By mid-December 1998, the fund had made a profit of $400 million after deducting fees paid to LTCM partners and staff.

There were press reports in early February 1999 of schisms among banks in the bailout consortium, with some wanting their money out by the end of the year and others content to “stay for the ride” for at least three years. There was also disagreement over how much Chase charged for a funding facility to LTCM. Within six months, there were reports that Meriwether and some of his team were planning to buy out the banks, with a little help from their friend Jon Corzine, who was set to leave Goldman Sachs after its IPO in May 1999.

By June 30, 1999, the fund had gained 14.1 percent, net of fees, since September of the previous year. Meriwether’s plan, which was approved by the consortium, was to redeem the fund, which was now valued at around $4.7 billion, and to launch a new fund focused on buyouts and mortgages.

LTCM repaid $300 million to its original investors who had a residual stake in the fund of approximately 9%. The consortium members each received $1 billion. Meriwether was bouncing back.

Following the LTCM disaster, blame-finding efforts naturally started. First in line were Meriwether and his market professors.

The banks together colluded to provide LTCM with more credit than they would provide a developing country. That combination of institutions’ and executives’ personal investment exposure was particularly unpleasant.

Merrill Lynch protested that $22 million in their employees’ funds wasn’t shady. Of the four investment vehicles an employee could select, LTCM was one of them. Despite that, it may have been more difficult for credit officers to be frank with LTCM. Investing in a company in which your financial gains are connected to your personal wealth is seen as crony capitalism.

The US Federal Reserve was third in line. Although only a small amount of public money was spent, it was implied that the Fed would provide liquidity until the markets had calmed down and become more rational. Wouldn’t this only encourage future hedge funds and lenders to be as risky?

The information flow was poor. Lack of LTCM’s activities and exposures being disclosed made it possible for it to borrow as much as it did. There was no method to find out how much LTCM was exposed to its other counterparties.

LTCM appears to have relied too heavily on theoretical market risk models, with very few of its capital being used for stress testing, gap risk, or liquidity risk. The portfolio managers assumed that the portfolio was sufficiently diversified to reduce risk.

LTCM risk managers thought that their derivatives’ net position bore no connection to the billions of dollars of underlying instruments. Instrument prices can vary independently, and instrument liquidity risk is always present.

The market apparently started trading against LTCM’s known positions. That seems a special plea. To have been just as merciless, Meriwether et al must have been in the markets for a long time.

A Missed Lesson

Every street on the block was blindsided by LTCM. This lesson was missed: application of initial margin for swaps and repos. They helped LTCM construct a complex layer of swap and repo positions. They believed their first-class collateral would adequately mitigate their loss if LTCM disappeared. LTCM was pushed closer to the brink by their margin calls to top up deteriorating positions. Global leverage and relationship of other counterparties weren’t part of their credit assessment of LTCM.

An LTCM working group had their findings reported in January, 1999 after the LTCM affair. It argued that the banks were highly exposed to an opaque entity. They placed a “heavily-placed reliance on collateralization of direct mark-to-market exposures.” This in turn allowed banks to compromise other key elements of effective credit risk management, such as upfront due diligence, methodologies for measuring exposure, limit setting, and ongoing monitoring of counterparty exposure, especially concentrations and leverage.

Also, banks’ covenants with LTCM required the posting of, or an increase in, initial margin even though the counterparty’s risk profile changed, for instance, as leverage increased. Another study issued in June, 1999 found that information-sharing and transparency could be greatly improved using various options. It noted the importance of measuring liquidity risk, and better market conventions and market practices, such as charging initial margin.

Banks and securities firms had narrow views about hedge funds, and LTCM was the primary example of this. The SEC appears to be concerned only with the risk posed by individual broker dealers, without considering the bigger picture, or even what’s going on in unregulated subsidiaries. Lindsey to the House Committee on Banking and Financial Services on October 1, 1998, noted: “The commission staff, the New York Stock Exchange, and others surveyed the major brokerage firms known to have exposure to hedge funds to learn about LTCM’s financial difficulties. We found that no single broker-dealer had LTCM’s regulatory capital or financial stability at risk. We learned that despite substantial amounts of credit being extended to LTCM by US securities firms, these loans were on a secured basis, with collateral collected and marked-to-market daily. Therefore, the banks lending to LTCM followed their normal lending practices. Most of the collateral came from highly liquid assets, such as treasury securities or G-7 country sovereign debt. LTCM covered any collateral shortfalls with margin calls. LTCM met all of its margin calls as of the date of the rescue plan. Additional evidence examined and reported to the commission shows that there was exposure to LTCM in non-US locations, such as the parent holding company or its unregistered affiliates.“

The unfortunate reality is that the SEC and the NYSE ignored the risk of the market’s aggregate exposure to LTCM, just like the firms themselves.

Was there a risk of moral hazard?

The simple answer is yes, because the LTCM bailout provided assurance that the Fed will intervene and mediate a solution, even if it does not commit funds. The Fed’s intervention may have also influenced Meriwether’s decision not to accept the offer from Buffett, AIG, and Goldman. The offer, despite being heavily conditional, demonstrates that the LTCM portfolio had a perceived market value. Negotiations between Buffett and Meriwether may have resulted in a price. Meriwether’s (and the Fed’s) argument is that Buffett’s deadline of 12:30 didn’t allow him enough time to consult with LTCM’s investors.

One could argue that a market solution was discovered. Fourteen banks contributed their own funds, viewing it as a medium-term investment with the potential for profit. From the standpoint of value preservation, it was a wise solution, even if it appeared to reward those whose recklessness had caused the problem.

Six days after the LTCM bailout, US Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan cut Fed fund rates by 25 basis points to 5.25 percent on September 29, 1999. On October 15, 1999, he reduced them by a quarter. His critics link these cuts directly to the LTCM bailout: it was an extra dose of medicine to ensure the recovery worked. According to some sources, the cut was prompted by rumors that another hedge fund was in trouble.

Lessons

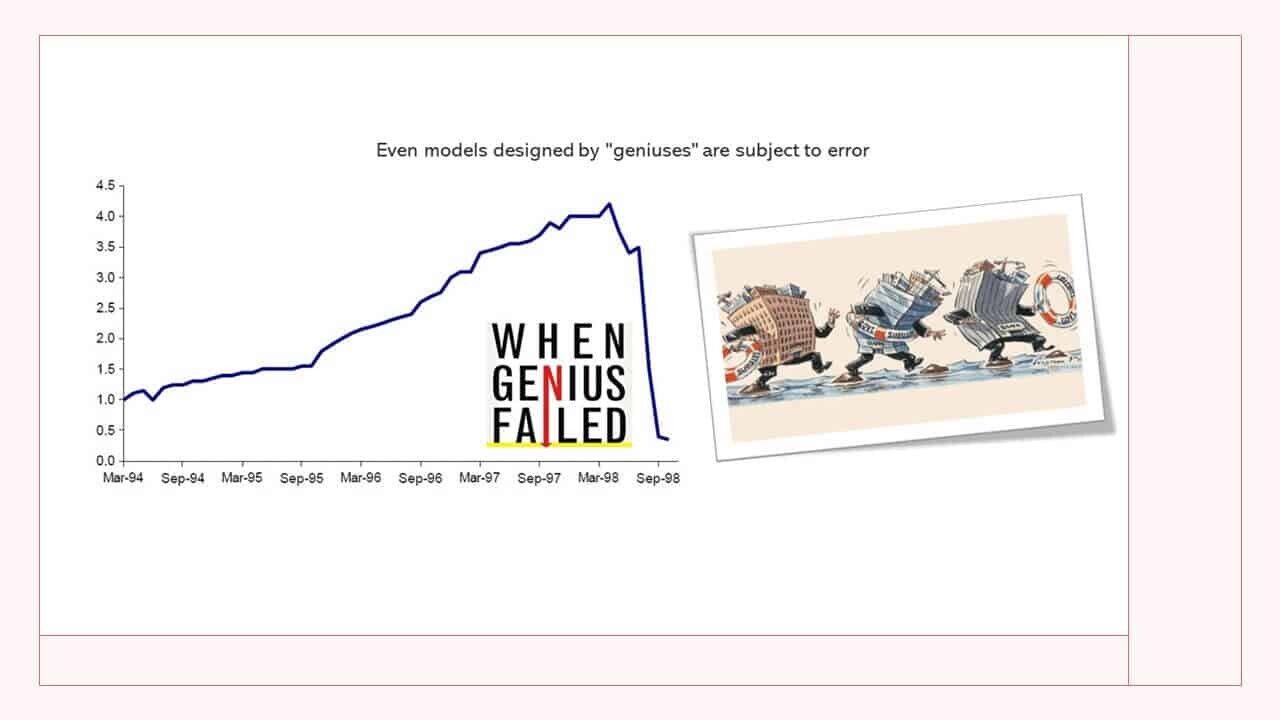

The models must be stress-tested and combined with judgement before being implemented.

For your own strategy development this means to test what happens when small changes are made to the strategy inputs, price data, or other elements of the strategy or the trading environment. In the case of an arbitrage strategy the test should include an analysis of the long run relationship between two assets and what happens if it takes more trading days for the pair to return to their long term equilibrium or what if Mr. Market becomes more volatile.

In this context the Monte Carlo approach is widely regarded as the most sophisticated VaR method. The MC method makes it easier to cope with extreme non-linearities as it allows for non-linear securities.

The LTCM debacle is a warning about the inadequacy of even the most sophisticated financial models, and suggests that stress tests and alternative approaches be used. We can also think about the ways in which judgement and stress-testing could have helped avoid or minimize this disaster.

The models used by LTCM predicted that the positions were low risk. When it comes to deciding whether to place a long or short position, judgements tell us that the key assumption that the models relied on was the high correlation between the long and short positions. After all, recent history has shown that different credit quality corporate bonds will move together (a correlation of between 90-95 percent over a 2-year horizon). However, the correlation dropped to 80% during the LTCM’s crisis. LTCM’s assumption of less leverage in the bet may have been stress-tested against this lower correlation.

However, if LTCM had thought to conduct a stress test on this correlation, as they did, it would not have had to create a stress situation out of thin air. LTCM might have used less leverage had they included this stress scenario in their risk management.

Risk management needs to be aggregated across institutions.

Financial institutions must learn a lesson: When aggregating risk across businesses, it is important to balance them against each other. A lot of the large financial institutions that were exposed to Russian crisis across a number of different industries learned about their similarities only after the LTCM crisis.

– – – –

References

Lowenstein, R., (2000), When Genius Failed: The Rise and Fall of Log-Term Capital Management. New York: Random House.

Mete Feridun (2006). Risk Management in Banks and Other Financial Institutions: Lessons from the Crash of Long-Term Capital Management (LTCM).Banks and Bank Systems, 1(3).

Shirreff, D., (2003), Lessons From the Collapse of Long Term Capital Management, The Risk Web Site [online]. Available from: http://risk.ifci.ch/146480.htm.

Stulz, R.M., (2000), “Why Risk Management Is Not Rocket Science”, Financial Times, Mastering Risk Series, June 27, 2000.