Ben Broadbent: Brexit and interest rates

Speech by Mr Ben Broadbent, Deputy Governor for Monetary Policy of the Bank of England, at the London School of Economics

Introduction and summary

Hello! It’s a real pleasure to come to the LSE to give this talk. It’s a great institution; I’m fortunate to have many friends here; last, but not least, it’s barely a hop and a skip from my office.

So thank you for having me. It won’t have escaped your attention that the MPC raised interest rates earlier this month. It did so, in part, because of the referendum-related decline in sterling’s exchange rate. That has pushed up CPI inflation and will continue to do for some time yet, as the rise in import costs is passed through to retail prices. Our remit says we can accommodate such effects, and take our time in bringing inflation back to target, but only so long we also think there’s spare capacity in the economy. As unemployment has declined that position has become harder to maintain.

We’ve been communicating this message for some time now. The MPC explained over a year ago that there were “limits to the extent to which above-target inflation [could] be tolerated” and that those limits depended on the degree of spare capacity in the economy. In March, eight months ago, it said in its Monetary Policy Summary that, if demand growth remained resilient, “monetary policy may need to be tightened sooner” than the market expected. Similar points were made in the intervening months.

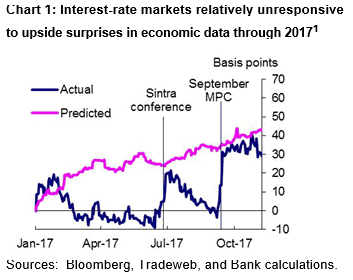

Yet, even as inflation rose, and the rate of unemployment fell further, interest-rate markets continued to under-weight the possibility that Bank Rate might actually go up this year. Chart 1 plots the cumulative change in the three-year sterling interest rate, over the past year or so, against what you might have expected to happen (based on historic correlations) given the pattern of data surprises.

There is always room for judgement about any individual interest-rate decision and not everyone on the Committee agreed with this one. After a long period of weak wage growth there’s certainly room for doubt, or at least caution, about the inflationary impact of lower unemployment. (For my part I think the evidence is still consistent with such an inflationary effect and I will say something about this later on.)

That uncertainty about wage formation may have been one thing that tempered the market’s reaction to stronger-than-expected economic data. But I suspect there was something else at work as well – and that’s Brexit. There’s been a persistent strain of opinion that EU withdrawal is something that necessarily means lower interest rates, or at least that it’s a reason to avoid putting them up. If so, then I think the belief has been overdone.

It’s not that the opposite is true. I’m certainly not going to argue here that interest rates will inevitably rise as Brexit proceeds. Apart from anything else, it isn’t the only show in town. Economic shocks come along all the time, in both directions. For example, one of the things that has sustained the UK economy over the past year or so, and to that extent contributed to the recent decision on interest rates, is the strength of the global recovery. On a UK-weighted basis, the world economy looks to have grown by almost 3% in the year to Q3, faster than for many years. This has nothing to do with Brexit and, if global growth were to falter, that too would have implications for the UK.

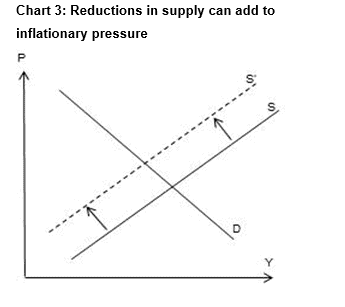

However, my main point is that, given all the moving parts, even the marginal impact of EU withdrawal on the appropriate level of UK interest rates is ambiguous. As the MPC said ahead of the referendum, in May 2016, the impact of a leave vote on monetary policy would depend on what it did to “demand, supply and the exchange rate”. These pull in different directions: holding fixed the other two, weaker demand tends to depress inflation and interest rates, declines in productivity and the exchange rate do the opposite. There are feasible combinations of the three that might require looser policy, others that lead to tighter policy.

You might say this is true at any time. “Demand, supply and the exchange rate” can always move around and it’s not as if monetary policy makers can ever afford to ignore any of them. The MPC is always having to think very carefully about the forces on aggregate spending; it generally has to form some sort of view about underlying supply growth; it must always take into account the latest moves in exchange rates and other asset prices.

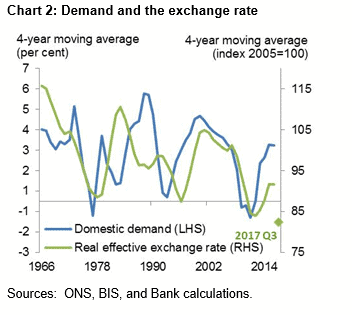

Furthermore, in the normal course of events these three things do not move independently of each other. It’s usually not valid to vary only one and imagine the others will stay constant. Exchange rates are volatile but, over time, they often move because of news about domestic demand (Chart 2 plots smoothed series for sterling’s real exchange rate and the growth of domestic demand). As for supply, identifiable news about future productivity is rare – we don’t often see things that cause people to reassess their forecasts of trend growth. In any case, it’s often assumed that any changes in underlying supply are sufficiently gradual that demand changes along with it, without the need for any prompting from monetary policy.

But the point we were trying to get across, when we used that phrase, is that Brexit has the capacity to move these things both significantly and, to an unusual extent, independently of each other. Today I want to pick out a couple of aspects of this.

One involves supply. As I say, economists often presume that changes in an economy’s underlying productivity occur only slowly. If so, it’s unlikely that any particular event – Brexit included – could change one’s view of short-term trends in underlying supply growth. But in one respect, at least, a sharp reduction in the degree of openness could have a more immediate impact. Suppose, plausibly, it results in a sudden shift in the demand for domestically produced output, away from what we’ve been exporting and towards goods and services we’ve hitherto been able to import. If, as seems likely, resources in different sectors are highly specialised – the physical and human capital suitable for one area aren’t as productive in others – the effect of this shift on aggregate supply is immediate. This is what the MPC was getting at when it said in the last Inflation Report that a “reduction and reorientation of trade and supply chains… may result in some existing supply capacity becoming obsolete.”

The second point involves the importance of expectations, something else the MPC has emphasised. At least until the formal date of departure, and possibly for some time afterwards, the effects of Brexit will depend centrally on what people expect it to do over the future. Those expectations are neither fixed nor uniform – some people are optimistic about its effects, others less so. It’s partly these differences in expectations that can lead to independent moves in demand and the exchange rate.

In particular, you can see the current inflation we’re experiencing as the result in part of a more pessimistic view of Brexit in financial markets – above all in the foreign exchange market – than among consumers.This gap in expectations helps to explain why, in Chart 2, the latest figure for the real exchange rate – the diamond towards the right of the graph – is well below the line for domestic demand growth. If the currency market had been as sanguine as households sterling would not have fallen as far, if at all, and inflation of import prices and the aggregate CPI would not have risen to the same extent. If, conversely, consumers shared the currency market’s more pessimistic view of the future, domestic demand would have been weaker and inflationary pressure would again have been lower.

Resource allocation and aggregate supply

Let me say a little more about these points, starting briefly with productivity. I want to offer a slight corrective to a view I often hear that, were there any wider supply effects from Brexit – things that either improve or impair the UK’s productive potential – these could only come through very slowly, too slowly to have any material bearing on monetary policy. The MPC typically concerns itself with policy horizons of 2-3 years. If only implicitly, it often has to form a view about the economy’s trend rate of growth over that period – its “speed limit”, in the language of the latest Inflation Report. But if any impact on potential output takes years to come through, it’s not clear that either the fact or the nature of Brexit should change those short-term estimates.

If you accept the way macro-economists often think about aggregate supply, this view makes sense. Typically, potential output is divided into a contribution from the stock of capital – how much physical capacity there is in the economy – and something called “total factor productivity”, or TFP. The stock of capital is much bigger than the flow of new investment that adds to it, and it therefore evolves relatively slowly. And, while TFP is a catch-all for all sorts of factors, many associate it with relatively slow-moving things like the state of technological knowledge or average educational attainment. On this basis it’s hard to see how the overall rate of potential output growth – and, a fortiori, our estimates of that trend – could change much over any short period of time.

Indeed, I think we can go further than this – not only can the view that changes in supply are gradual make sense in principle, I think it’s usually true empirically as well. Over shorter-run cyclical horizons, most movements in economic growth appear driven by demand, not supply. That’s why inflation tends to be higher in upturns than downturns.

But that doesn’t mean such short-term hits to productivity are inconceivable. We saw a sharp step down in productivity growth after the financial crisis. And I think there are things involved in Brexit that, once one digs below the macro-economic surface, could potentially do the same.

I’m thinking in particular of allocative effects. If EU withdrawal results in significant new barriers to trade between the UK and its major trading partners in the rest of Europe, one plausible consequence would be a marked shift in relative demand for UK output. The economy would probably experience less demand for the things we’ve been exporting to the EU and more for UK-based substitutes for the goods and services we’ve tended to import.

That wouldn’t matter much if the resources for one could be seamlessly and costlessly transferred to the other. In reality, however, those resources, human as well as physical, are likely to be specialised: they’re more productive in some areas than others. A plant used to produce a particular car part, as part of an integrated European supply chain, cannot suddenly be converted into one that makes a complex German machine tool. A field currently producing barley, sold into the European market, can’t easily or as fruitfully be replanted with olive trees. Someone steeped in one particular area of financial services cannot overnight, or costlessly, be reborn as an expert widget-maker, able to generate the same contribution to GDP. In the presence of specialised inputs a significant shock to relative demand can have coincident and material effects on aggregate supply.

The general lesson here is that “total factor productivity” doesn’t just depend on aggregate resources. To the extent those resources are specialised it also depends on their allocation. I wondered some years ago whether such effects were at work after the financial crisis. Given the potential reallocative effects of any material change in the UK’s trading arrangements, it’s conceivable they could arise in this case too.

Indeed it’s possible they could arise even ahead of the formal date of the UK’s departure. In September/ October a CIPS survey of procurement managers suggested there could be significant unwinding of supply chains through the course of next year: 40% of UK firms who currently use EU suppliers are actively looking for domestic alternatives; the equivalent figure in the other direction – the proportion of European businesses expecting to move away from existing UK suppliers – is 63%. A CBI survey in October found that, in the absence of a transition deal, 60% of firms would begin to activate “worst-case” contingency plans by the end of March 2018, a full year before the UK’s exit.

Let me now turn to the point about expectations. This is of particular relevance for the current inter-regnum, the period following the referendum but before Brexit itself. At least until the formal departure date what people expect of it is the main way – arguably the only way – in which it can affect the economy.

This is an obvious point. But I think we should pay it some heed, not least because it’s unclear how these expectations will evolve. If it’s not a unique event Brexit is certainly an exceptional one. People haven’t much history to go on. It’s therefore reasonable to imagine that predictions about its consequences might vary over time: we will all of us learn more about its effects as Brexit unfolds. It’s also understandable if these expectations differ across the population.

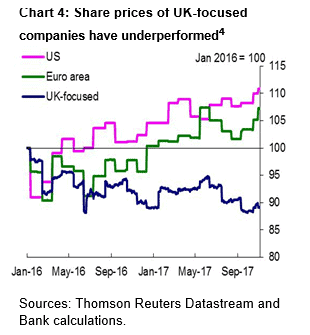

It’s clear that financial markets have relatively pessimistic expectations. Since the referendum share prices of UK-focused companies have significantly under-performed both their international peers and those of companies quoted in the UK but whose earnings come from overseas (Chart 4).

Sterling’s exchange rate has also fallen very sharply. As I said in a talk earlier this year, I think this is because the foreign exchange market has decided that leaving the EU will reduce productivity in the UK’s tradable sector or raise its costs in some other way.

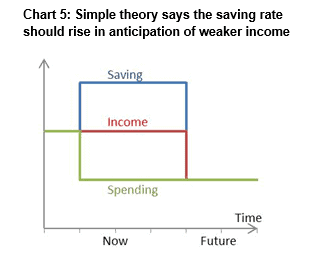

But it’s far from clear that, as measured by their actual spending patterns, expectations among households are anything like as pessimistic. Chart 5 is an extremely stylised representation of how, in the simplest models used by economists, consumption responds to negative news about future income.

In this set-up consumers are assumed to want to smooth their spending. Rather than responding to every temporary up and down, they match their spending to what they expect their average income to be over the future. As a result, anticipated changes in long-run income should matter more than temporary fluctuations in current income. On this view, someone who thinks his or her income will be persistently lower from tomorrow would reduce the level of spending today. In the interim – until income actually declines – the saving rate goes up. So the behaviour of the saving rate should tell you something about how consumers expect income to evolve over the future. Expectations of strong income growth lower the saving rate, a more pessimistic view does the opposite.

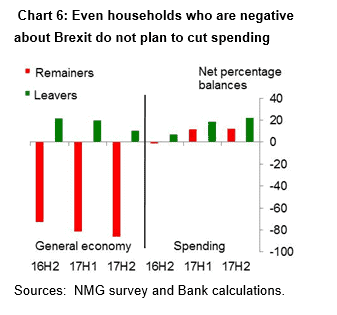

Now we know that, in the real world, there are reasons why consumption doesn’t exactly behave like this. We also know, from our own NMG survey of households, that there are many households who do say they expect EU withdrawal to have a negative impact. Since September last year this biannual survey has included three Brexit-related questions. One asks for your overall opinion – do you think leaving the EU is a good or a bad idea? (One would imagine the responses here are well correlated with what people actually voted in the referendum; consistent with that, the households surveyed in September 2016 were more or less split down the middle on this question.) The second asks about the impact of Brexit on the economy, the third asks how households expect the referendum result to affect their spending.

The balances on these last two questions are drawn in Chart 6.

They’re divided between those who answered the first question positively, in green – let’s call them the “leavers” – and the “remainers” in red. Perhaps we shouldn’t be too surprised by the first panel. The “leavers” tend to foresee a positive economic impact, the “remainers” the opposite. The “remainers” are apparently more uniform in their answers: adding them up, the balances in the aggregate sample are also negative.

What’s striking, however, is that there’s no Brexit-induced cut in planned spending, even for the “remainers”. We need to be a little careful here, as it’s not clear whether people are telling us about their spending in real or in nominal terms. If it’s the latter then, allowing for inflation, perhaps some of the bars might turn negative when measured in real terms. But, on the face of it, there is very little correspondence between people’s views about the economic impact of Brexit and their consumption plans, and no anticipated response of spending for the sample as a whole. Whatever the reason – perhaps, given all the myriad uncertainties involved, people’s professed expectations of Brexit are too imprecise to matter for current decisions – it’s apparent from this survey that households have been relatively relaxed about the process, at least compared with the foreign exchange market. Measured by what really counts – their consumption – households’ effective expectations haven’t shifted as much, if at all.

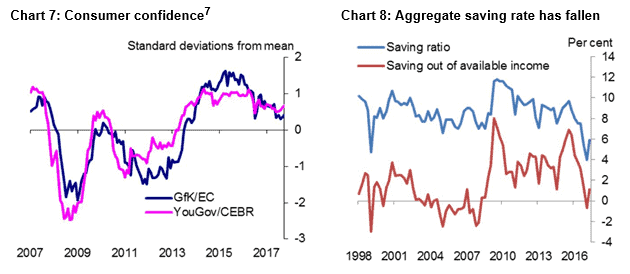

The same is apparent in consumer confidence surveys, which are still close to historic averages (Chart 7), and in the hard data. According to national accounts estimates the household saving rate has actually fallen since the referendum (Chart 8) and consumption has continued to grow.

The resultant combination of a weak exchange rate and relatively resilient domestic demand, clearly apparent in Chart 2, has had consequences for inflation. If the foreign exchange market had been as sanguine as households, we would not have witnessed anything like the same rise in import prices, or the import-sensitive parts of the CPI, that we have done. Conversely, the rise in inflation would also have been smaller had households’ effective expectations been as pessimistic as those in the foreign exchange market.

Let me expand on this. The first point is illustrated well enough by recognising the importance of sterling’s depreciation for inflation. Our estimates suggest that “pass-through” from the depreciation added around ¾% point to the CPI in the year to 2017 Q3. It’s also had effects on demand, some positive, some negative. But I think it’s safe to say that, without the depreciation, inflation would be much closer to target. Other things have also contributed the rise over the past year, notably the rise in oil prices.

In May 2016, ahead of the referendum and prior to sterling’s fall, the MPC’s central forecast for inflation in 2017 Q3 was below the 2% target. The second point – how inflation would also have been lower had households been as pessimistic as the foreign exchange market – is harder to get across, because you have to simulate the behaviour of consumption. I’m going to try and do that with a simple economic model.

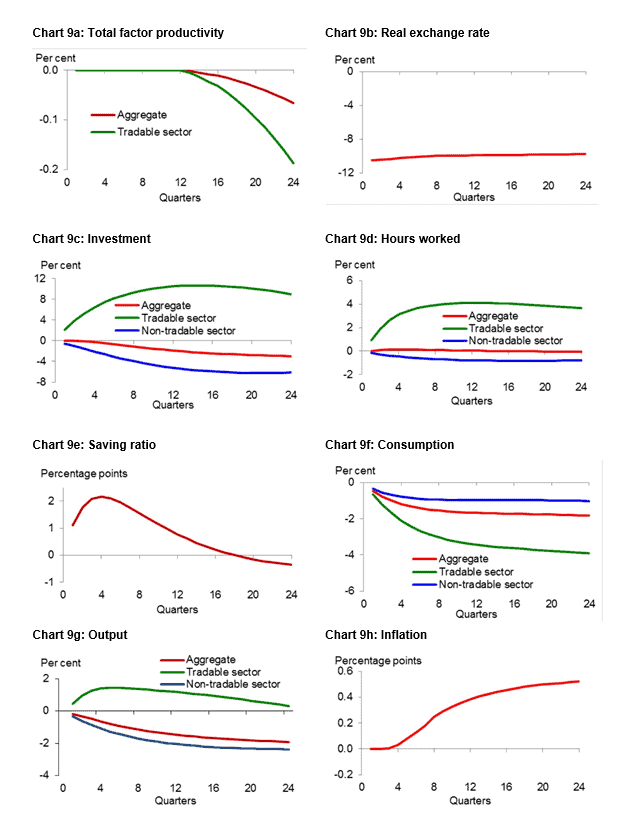

We’ll imagine an economy that has two sectors – one third of it produces internationally tradable output, two thirds non-tradable stuff – between which capital and people can move costlessly. We’re going to hit the economy with negative news about the future8. Specifically, we’ll suppose that people suddenly learn that, three years hence, productivity in the tradable sector is going to start to fall (relative to base). To fix the numbers, we’ll scale the hit so as to produce a material decline in the fair value of the exchange rate – 10%, say. Given the other parameters in the model, this requires an anticipated and overall decline in labour productivity of around 8% in the tradable sector, 5% in the economy as a whole. The results of the simulation are shown in Charts 9(a)-(h)9.

Because the foreign exchange market fully and correctly anticipates the productivity hit the depreciation occurs immediately and does nothing further when productivity actually falls (9(b)). In the interim, the weaker currency provides a big fillip to the tradable sector. Its sterling profits rise significantly and, for as long as productivity holds up, this encourages a significant expansion in investment, employment and output (the green lines in 9(c),(d) and (g)). This is the “sweet spot” I referred to in the talk I gave about sterling earlier this year.

I should emphasize that there’s nothing in this simple model that inhibits the response to this sweet spot. New investments are assumed to be costlessly reversible – firms can easily get out of them once productivity starts to decline – capital and labour can be easily moved from one sector to the other and there’s complete certainty about the timing and scale of that event. All this means that tradable output responds powerfully to the depreciation and, on the demand side, net trade and investment grow significantly. In reality, perhaps because there are significant frictions and uncertainties in the real world, the actual response of the tradable sector has been much more modest (even though the fall in the exchange rate has been bigger than 10%).

But there’s also a significant difference in the predicted behaviour of consumption, this time in the opposite direction. Because they agree about the coming hit to income, households cut their spending immediately in this simulation – it falls 1½% in the year after the news comes through – and the saving rate goes up. This dominates the sizeable response of net trade and investment, such that aggregate demand and output also decline. As a result the response of inflation is relatively muted. It still rises, thanks to the weaker exchange rate. But it does so by only 0.5% points, significantly less than we’ve seen over the past year or so. With output declining and inflation close to target it’s not clear the MPC would have wanted to raise interest rates.

The point that comes across, for me, is that inflation would be lower had effective expectations of the implications of Brexit, across different parts of the economy, been more uniform.

Let me be clear. I’m not saying one side or the other – households and financial markets – is “wrong” or “right”. We don’t yet know. My points are rather that for as long as we don’t know the ultimate Brexit outcome, it’s understandable that expectations should differ and that the particular difference we’ve seen since the referendum, with the foreign exchange market more pessimistic than the real economy, has been inflationary, and the gap in expectations has therefore been an important contributor to the recent rise in inflation and therefore interest rates.

A corollary is that at least until Brexit actually happens, its significance for inflation and interest rates derives not so much from the process itself but from whether those expectations move closer together or further apart. However it occurs, whether via a stronger exchange rate or weaker consumption, a degree of reconciliation would tend to lower inflationary pressure. Further divergence would do the opposite. I think it’s hard to predict which of these is more likely.

Some remarks about wage growth and unemployment: don’t forget productivity

One consequence of being uncertain about supply growth, for a monetary policy maker, is that you begin to rely somewhat less on indicators of economic growth – it’s no longer so clear what constitutes a “strong” or a “weak” GDP print, relative to underlying productivity – and instead put more weight on direct measures of spare capacity, such as unemployment.

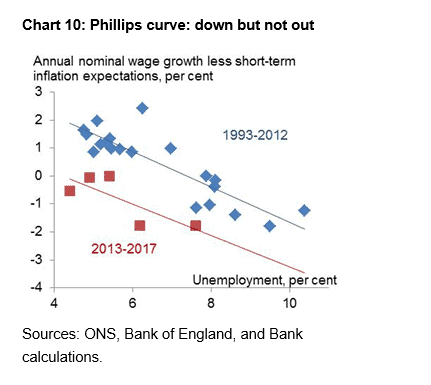

However, that’s advisable only to the extent you trust the link between unemployment and wage growth. In recent years, many seem to have lost that trust. According to the “Phillips curve”, low unemployment is meant to push up wage growth. Yet here we are with unemployment at a four-decade low and wages still growing at a rate well below the historical average. As a result, several commentators have questioned the MPC’s central prediction that wage growth will rise next year. Some have gone further and pronounced the death of the Phillips curve.

There are always risks to any forecast. But the latter claim, at least, is premature. Using annual data, Chart 10 plots UK wage growth, less expected inflation, against the rate of unemployment – the UK’s Phillips curve. The blue dots cover the first twenty years of inflation targeting, till 2012, the red dots the five years since. The estimated regression line has clearly shifted to a lower position since the crisis and the period of weaker productivity growth that has ensued.

However, if people come to accept the implications of that weaker productivity trend for the real wage increases they can expect to receive – the “norm” for real pay growth being one thing that determines the position of the Phillips curve – that’s precisely what you’d expect to see. It would also shift leftwards if structural improvements in the labour market had lowered the equilibrium rate of unemployment. The MPC reduced its estimate of that equilibrium rate, from 5% to 4½%, in February.

In real time, as it’s happening, it’s statistically difficult to distinguish a shift from a flattening and there is clearly room for caution about our forecasts for growth of wages and unit costs.

But, over time, I think the evidence looks more in favour of the former. The curve still seems to have a slope – all else equal, a tighter labour market is likely to mean faster wage growth.

I was in Aberdeen earlier this year and, when asked by a wily reporter what I planned to vote at the following MPC meeting, fobbed off the question by referring to a number of “imponderables” – (Some people came back to me claiming this wasn’t a word. It is. Those readers who’ve got this far deserve some light relief. Thanks to the wonders of technology I found a long list of “imponderables” on the internet, compiled by an engineer in New Mexico – see http://www.unm.edu/~jerome/imponder.htm. I don’t know that these are any more or less insoluble than the impact of Brexit on interest rates, but they’re certainly (at least) as entertaining.)

I was in Aberdeen earlier this year and, when asked by a wily reporter what I planned to vote at the following MPC meeting, fobbed off the question by referring to a number of “imponderables” – (Some people came back to me claiming this wasn’t a word. It is. Those readers who’ve got this far deserve some light relief. Thanks to the wonders of technology I found a long list of “imponderables” on the internet, compiled by an engineer in New Mexico – see http://www.unm.edu/~jerome/imponder.htm. I don’t know that these are any more or less insoluble than the impact of Brexit on interest rates, but they’re certainly (at least) as entertaining.)

I’ve talked about some of those today. The combination of low unemployment and weak wage growth might qualify as one, but I think low productivity growth can explain quite a bit of that particular puzzle. We’ve had only limited data since productivity flattened out, a few years ago, and if you estimate a Phillips curve only over that period the resulting estimates are bound to be imprecise. But, to my mind, the basic judgement in the MPC’s forecast – that, for given productivity growth, less slack leads to faster wage growth – still looks reasonable.

The effects of Brexit on inflation, and ultimately on the appropriate level of interest rates, are altogether more uncertain and more complex. They’re certainly too complex to justify the simple assertion that Brexit necessarily implies low interest rates. The MPC eased policy in August 2016 not because of the referendum result but because of the steep fall in measures of business and consumer confidence that followed it. We made the judgement that the risks to demand were such that, even allowing for the weaker exchange rate and any immediate effects on supply, Bank rate should be reduced.

But there’s no inevitability about the balance of these effects. I’ve described how the current inflation is in part the result of a divergence between the effective expectations of consumers and those in financial markets. If those expectations were to re-converge, from either end, inflationary pressure would diminish. If they diverge further the opposite would happen. Firms’ expectations will affect their investment and purchasing decisions, and these in turn can have an impact on productivity. Some of those effects could come through faster than people often assume. If they do, then even the argument that Brexit lowers growth and therefore interest rates isn’t watertight. And, to add something else to these risks, something I haven’t dealt with in this speech, a sudden switch to WTO trading rules would involve the immediate imposition of tariffs on imports, further raising their cost.

Predicting others’ predictions isn’t easy, and I don’t think the balance of risks to inflationary pressure, and therefore future interest rates, is obvious. In the meantime, the MPC has little choice, it seems to me, but to take the economic data at face value. To adapt the football manager’s cliché, we can only play the economy that’s in front of us. What’s been in front of us for several months is an economy with above-target inflation and dwindling spare capacity. That’s why I think it was the right thing to remove a degree of monetary accommodation. And while things might change – they always do – we will continue to act in a way that ensures stable inflation over the medium term while still providing what support we can to jobs and economic activity.

Thank you.