Ed Thorp’s Remarkable Journey: From Beating Casinos to Dominating Wall Street

Ed Thorp, often called the father of quantitative investing, is one of the rare figures to master both gambling and financial markets with scientific precision. Long before the rise of Wall Street quants and algorithmic hedge funds, Thorp was quietly turning chaos into order. His story isn’t just about outsmarting roulette wheels and stock tickers it’s about building an edge where most saw randomness.

Cracking the Casino Code

Thorp’s journey began at the roulette table not as a gambler, but as a strategist. Armed with a homemade wearable computer, he gained an astounding 44% edge in roulette. But it was in blackjack that he left a lasting legacy. With the publication of Beat the Dealer, he introduced the world’s first card counting system, turning what had been a game of chance into a game of odds.

His ideas reshaped the gambling world and paved the way for a new kind of player one who didn’t rely on luck, but on statistical edge.

From Blackjack to Hedge Funds

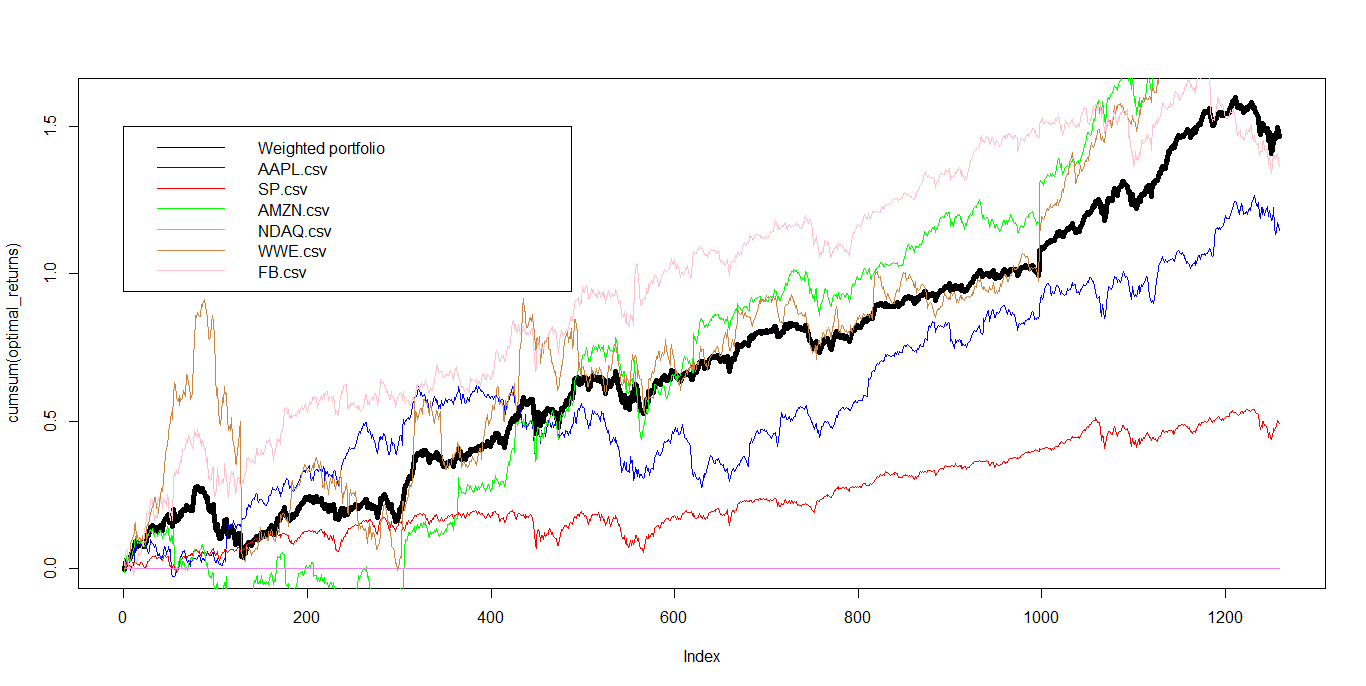

It wasn’t long before Thorp realized the same probabilistic thinking could be applied to the markets. He launched Princeton Newport Partners, one of the earliest quantitative hedge funds. Over nearly two decades, it delivered a 19.1% annualized return, outpacing the S&P 500 by a wide margin and doing it with a level of risk control that stunned traditional fund managers.

From 1992 to 2002, Thorp ran a second fund that returned 18.2% per year, proving his methods were no fluke. Long before Black-Scholes became standard, Thorp was already using option pricing models and exploiting inefficiencies through arbitrage, making him a pioneer of modern quant finance.

The 1987 Crash: Calm in the Eye of the Storm

Black Monday stands etched in history as a day of sheer panic for most traders. But for Ed Thorp, it was an entirely different story. As the crash sent shockwaves through the financial world, Thorp was in the midst of his daily lunch date with his wife, Vivian.

Amidst the chaos, Thorp remained composed and unruffled. When the office urgently called to report the unfolding market turmoil, he didn’t betray even a hint of anxiety. Thorp’s calm demeanor was a testament to his meticulous preparation. He had painstakingly considered and accounted for all potential market scenarios, even the most catastrophic ones like the Black Monday crash.

Rather than succumbing to panic, Thorp calmly finished his lunch with Vivian and then retreated to the sanctuary of his thoughts. There, in the tranquility of his home, he embarked on a mission to exploit the situation that had engulfed the financial world.

After thinking hard about it overnight I concluded that massive feedback selling by the portfolio insurers was the likely cause of Monday’s price collapse. The next morning S&P futures were trading at 185 to 190 and the corresponding price to buy the S&P itself was 220. This price difference of 30 to 35 was previously unheard of, since arbitrageurs like us generally kept the two prices within a point or two of each other. But the institutions had sold massive amounts of futures, and the index itself didn’t fall nearly as far because the terrified arbitrageurs wouldn’t exploit the spread. Normally when futures were trading far enough below the index itself, the arbitrageurs sold short a basket of stocks that closely tracked the index and bought an offsetting position in the cheaper index futures. When the price of the futures and that of the basket of underlying stocks converged, as they do later when the futures contracts settle, the arbitrageur closes out the hedge and captures the original spread as a profit. But on Tuesday, October 20, 1987, many stocks were difficult or impossible to sell short. That was because of the uptick rule.

It specified that, with certain exceptions, short-sale transactions are allowed only at a price higher than the last previous different price (an “uptick”). This rule was supposed to prevent short sellers from deliberately driving down the price of a stock. Seeing an enormous profit potential from capturing the unprecedented spread between the futures and the index, I wanted to sell stocks short and buy index futures to capture the excess spread. The index was selling at 15 percent, or 30 points, over the futures. The potential profit in an arbitrage was 15 percent in a few days. But with prices collapsing, upticks were scarce.

What to do? I figured out a solution. I called our head trader, who as a minor general partner was highly compensated from his share of our fees, and gave him this order: Buy $5 million worth of index futures at whatever the current market price happened to be (about 190), and place orders to sell short at the market, with the index then trading at about 220, not $5 million worth of assorted stocks—which was the optimal amount to best hedge the futures—but $10 million. I chose twice as much stock as I wanted, guessing only about half would actually be shorted because of the scarcity of the required upticks, thus giving me the proper hedge. If substantially more or less stock was sold short, the hedge would not be as good but the 15 percent profit cushion gave us a wide band of protection against loss.

In the end we did get roughly half our shorts off for a near-optimal hedge. We had about $9 million worth of futures long and $10 million worth of stock short, locking in $1 million profit. If my trader hadn’t wasted so much of the market day refusing to act, we could have done several more rounds and reaped additional millions.

Spotting Unique Opportunities

Thorp’s knack for identifying unique opportunities extended beyond traditional markets. He invested in oil tankers when they were selling for scrap value, reaping substantial returns as demand for tankers fluctuated.

Along with Jerry Baesel, the finance professor from UCI who joined me at PNP, I spent an afternoon with Bruce in the 1980s in his Manhattan apartment discussing how he thought and how he got his edge in the markets. Kovner was and is a generalist, who sees connections before others do.

About this time he realized large oil tankers were in such oversupply that the older ones were selling for little more than scrap value. Kovner formed a partnership to buy one. I was one of the limited partners. Here was an interesting option. We were largely protected against loss because we could always sell the tanker for scrap, recovering most of our investment; but we had a substantial upside: Historically, the demand for tankers had fluctuated widely and so had their price. Within a few years, our refurbished 475,000-ton monster, the Empress Des Mers, was profitably plying the world’s sea-lanes stuffed with oil.

I liked to think of my part ownership as a twenty-foot section just forward of the bridge. Later the partnership negotiated to purchase what was then the largest ship ever built, the 650,000-ton Seawise Giant. Unfortunately for the sellers, while we were in escrow their ship unwisely ventured near Kharg Island in the Persian Gulf, where it was bombed by Iraqi aircraft, caught fire, and sank.

The Empress Des Mers operated profitably into the twenty-first century, when the saga finally ended. Having generated a return on investment of 30 percent annualized, she was sold for scrap in 2004, fetching almost $23 million, far more than her purchase price of $6 million.

Capitalizing on the SPAC Opportunity

In the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, Thorp capitalized on a unique opportunity presented by SPACs (special purpose acquisition corporations). Often dismissed by many, these closed-end funds offered a chance to purchase assets at a discount.

An unusual opportunity to buy assets at a discount arose during the financial crash of 2008–09, in the form of certain closed-end funds called SPACs. These “special purpose acquisition corporations” were marketed during the preceding boom in private equity investing. Escrowing the proceeds from the initial public offering (IPO) of the SPAC, the managers promised to invest in a specified type of start-up company.

SPACs had a dismal record by the time of the crash, their investments in actual companies losing, on average, 78 percent. When formed, a typical SPAC agreed to invest the money within two years, with investors having the choice—prior to the SPAC buying into companies—of getting back their money plus interest instead of participating.

By December 2008, panic had driven even those SPACs that still owned only US Treasuries to a discount to NAV. These SPACs had from two years to just a few remaining months either to invest or to liquidate and, before investing, offer investors a chance to cash out at NAV. In some cases we could even buy SPACs holding US Treasuries at annualized rates of return to us of 10 to 12 percent, cashing out in a few months. This was at a time when short-term rates on US Treasuries had fallen to approximately zero!

Navigating Runaway Inflation

Ed Thorp’s “runaway inflation trade” was a shrewd strategy he employed during a period of soaring inflation and remarkably high interest rates in 1981. Here’s a breakdown of how this trade worked:

- Inflation and High Interest Rates: In 1981, the United States was grappling with runaway inflation. Short-term U.S. Treasury bills were yielding nearly 15 percent, and fixed-rate home mortgages had skyrocketed to over 18 percent per year. These extraordinary interest rates were a response to the rapidly rising prices in the economy.

- Gold Futures Market Opportunity: Thorp identified an opportunity within the gold futures market, which was influenced by the prevailing economic conditions. Gold is often seen as a hedge against inflation and tends to rise in value when inflation is rampant.

- Price Discrepancy: Thorp observed a significant price discrepancy in the gold futures market. Specifically, he noticed that gold futures contracts for delivery two months in the future were trading at a price of $400 per ounce, while contracts for delivery fourteen months out were trading at $500 per ounce. This price gap presented a lucrative opportunity.

- The Trade: Thorp’s trade strategy was straightforward. He decided to buy gold at the lower price of $400 per ounce for delivery two months in the future. This meant that he committed to purchasing gold at this price with the expectation of taking possession of it in two months.

- Profit Potential: Once Thorp acquired the gold at $400 per ounce, he held onto it for a nominal cost over the course of a year. After that year, he could deliver the gold, which had appreciated in value, for $500 per ounce. This meant he would gain a 25 percent profit in just twelve months.

The key to this trade was capitalizing on the price disparity between the short-term and long-term gold futures contracts, which was driven by the market’s anticipation of future inflation. By purchasing gold at a lower price and benefiting from its price appreciation over time, Thorp was able to leverage the extraordinary economic conditions to generate substantial returns.

This trade is a masterclass in opportunistic thinking. Rather than guessing market direction, Thorp studied inefficiencies born from macroeconomic extremes and then calmly constructed a high-conviction, low-risk play.

It’s a timeless reminder for traders today: the real edge often lies in what others overlook.

Market Efficiency According to Thorp

Beyond the Illusion of Efficiency: Thorp’s Take on Market Predictability

While many academics of his time rallied behind the Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH), Ed Thorp took a more nuanced stance. He didn’t reject market efficiency outright — instead, he reframed it:

“Markets are only efficient relative to what the observer knows.”

In other words, what looks like randomness to one trader may appear as opportunity to another with better information or sharper tools. For Thorp, markets weren’t chaotic — they were just waiting to be decoded.

Technicals + Fundamentals: A Winning Combo

In the mid-2000s, long after most would’ve retired, Thorp was still refining strategies. He developed a trend-following system for the futures market that blended technical indicators with fundamental macro insights. This hybrid approach outperformed traditional models — proving that the marriage of momentum signals with real-world economic data can produce a potent trading edge.

While many quants worship clean math and ignore messy fundamentals, Thorp understood that real edge often lies in context — not just code.

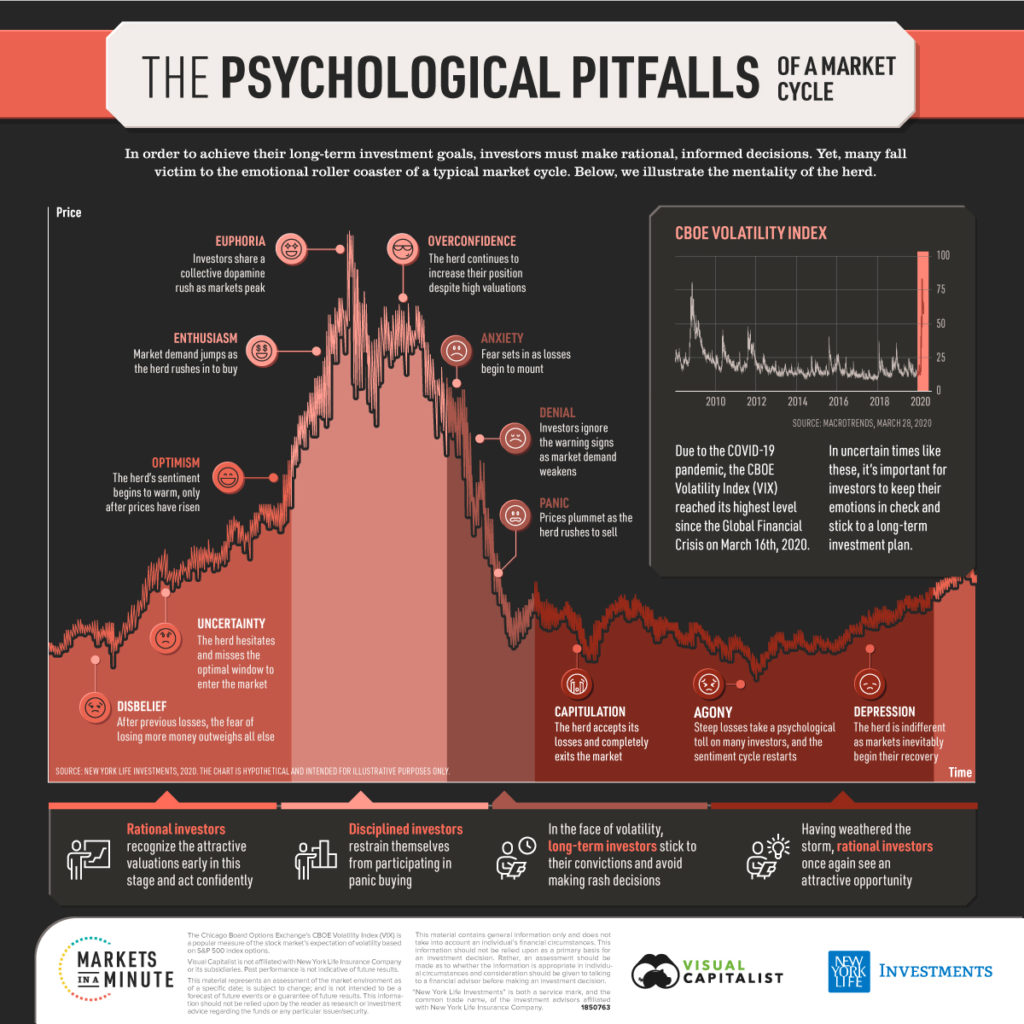

Mind Over Market: Anchoring and Emotional Detachment

One of Thorp’s most practical lessons for traders is deceptively simple:

Don’t anchor to your entry price.

He warned against letting emotions cloud decision-making. Getting fixated on a specific entry point often leads to poor exits, missed opportunities, or worse — holding losers out of stubborn pride. Thorp championed flexibility over ego, urging traders to detach from sunk costs and refocus on current market dynamics.

Decoding Headlines: Hype vs. Signal

Thorp also taught traders to approach financial media with skepticism. Market headlines, especially during volatile periods, tend to amplify noise and exaggerate minor movements.

The savvy trader, in Thorp’s view, reads between the lines. Ask:

- Is this a real catalyst?

- Or just a narrative built around price action?

This mental filter helps traders avoid reactive decisions and focus on data-driven conviction.

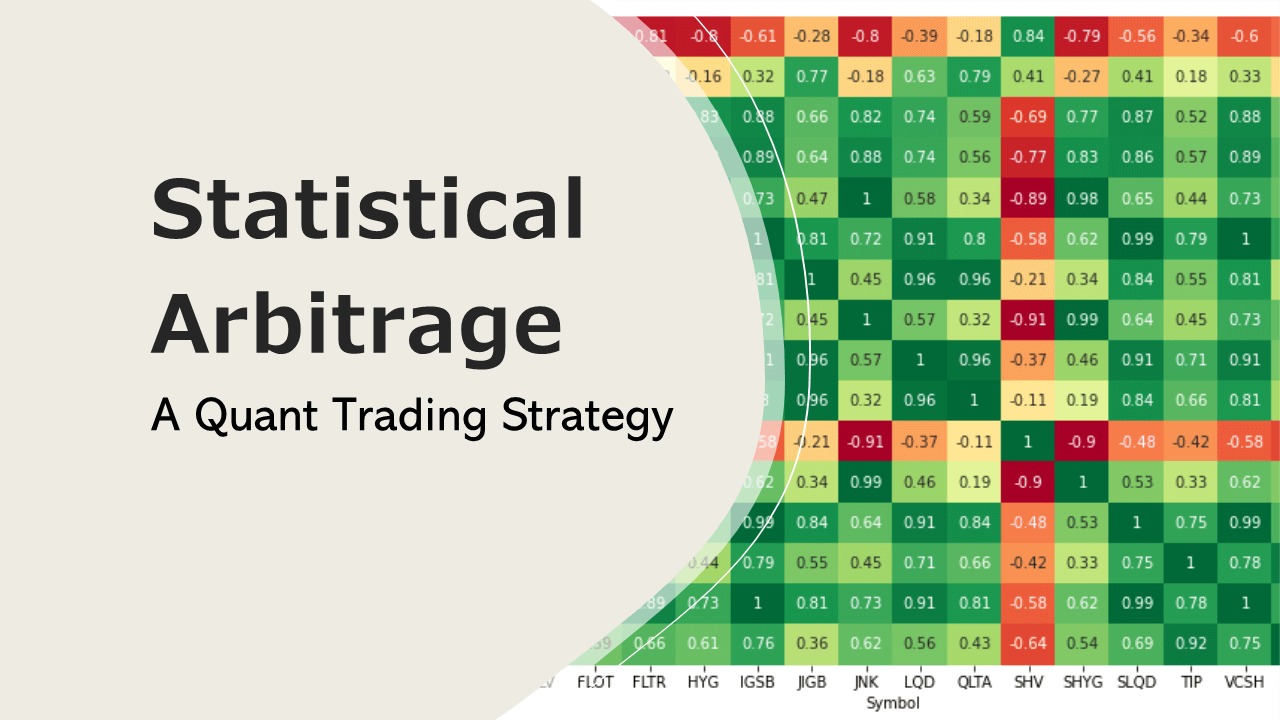

Correlation: The Invisible Risk

One of Thorp’s enduring contributions to portfolio management was his emphasis on correlation. It’s not enough to diversify across positions — what matters is how those positions interact during stress.

By selecting assets with low or negative correlation, traders can reduce drawdowns, smooth volatility, and dramatically improve risk-adjusted returns. Thorp’s portfolios were never just diversified — they were engineered for resilience.

Leverage: Power, With Boundaries

Thorp wasn’t anti-leverage — he simply treated it with the respect it deserves. While leverage can magnify gains, it also magnifies fragility. His advice?

- Use leverage selectively.

- Know your downside before you size up.

- Be honest about your emotional and financial capacity to handle outliers.

In Thorp’s world, leverage is a tool — not a ticket to ruin.

Unveiling the Kelly Criterion: A Money Management Formula

One of the cornerstones of Thorp’s trading success was his adept use of the Kelly Criterion, a money management formula designed to optimize position sizing. Here’s a detailed breakdown of how it works:

The Kelly Criterion is a mathematical formula that helps traders determine the optimal fraction of their capital to invest in a single trade. It is calculated as:

k% = (bp–q)/b, with p and q equaling the probabilities of winning and losing, respectively.

Where:

- k% is the fraction of capital to be invested.

- b is the net odds received on the trade (the ratio of profit to loss).

- p is the probability of winning the trade.

- q is the probability of losing the trade (1 – pp).

Let’s illustrate this with an example:

Suppose a trader has identified a trade with a 60% chance of winning (p=0.60) and a 40% chance of losing (q=0.40). The trade offers a 1:1 reward-to-risk ratio (b=1)).

Using the Kelly Criterion formula:

k%=((1⋅0.60)−0.40))/1 =0.20

In this example, the optimal fraction of capital to invest in the trade is 20%. This means that the trader should allocate 20% of their capital to this particular trade.

Risk Management During Drawdowns

For Ed Thorp, managing risk wasn’t just about reducing exposure — it was about preserving the ability to play the next hand.

During drawdowns, Thorp advised gradually reducing position sizes in proportion to cumulative losses. Rather than clinging to positions in hopes of a rebound, his philosophy was rooted in mathematical survival: when volatility spikes or losses accumulate, the priority becomes capital preservation over recovery attempts.

“The key is not to get rich quick. It’s to stay in the game long enough to get rich.”

This conservative scaling-down approach ensures traders can weather bad streaks without being forced out of the market entirely — a concept borrowed from his background in blackjack, where risk of ruin is ever-present for the reckless.

From Casino Floors to Wall Street Floors

Ed Thorp’s journey — from beating the house in Las Vegas to building market-beating hedge funds — remains one of the most unique trajectories in finance. His ability to merge mathematics, logic, and probability into real-world trading edge is still a blueprint for serious traders.

His career offers more than strategy — it offers a mindset: intellectual humility, adaptability, and the commitment to deep research before placing any bet.

Thorp proved that innovation plus discipline can generate lasting outperformance — even in the world’s most competitive arenas.

Gaining an Edge in Trading: The Path to Sustainable Success

In Thorp’s world, trading without an edge is gambling — and the house always wins. The concept of an “edge” is the cornerstone of his entire philosophy, and it’s not just about finding it — it’s about understanding it, proving it, and executing with consistency.

In his book A Man for All Markets, Thorp lays out how and where inefficiencies arise, and more importantly, how smart traders can systematically exploit them.

Where Inefficiencies Come From

Despite decades of academic theory claiming markets are efficient, Thorp found them anything but — especially when viewed through the lens of a creative, well-informed observer.

He identified four major sources of market inefficiency:

1. Information Asymmetry

Markets move on who knows what — and when. Those with faster, more accurate access to information have a measurable edge over slower participants. Thorp emphasized that news does not hit all traders equally or simultaneously, creating short-lived windows of opportunity.

2. Limited Financial Rationality

Not every market participant is rational — in fact, most aren’t. Emotional biases, heuristics, and herd behavior dominate decision-making, especially in retail trading. Thorp knew that by maintaining rationality and discipline, traders could exploit the irrational moves of others.

3. Incomplete Information

Traders rarely operate with the full picture. Prices reflect a mosaic of incomplete data points, and edge often comes from the ability to fill in the missing pieces faster — or more accurately — than the competition. Thorp’s strategies always incorporated probabilistic thinking and working with incomplete information intelligently.

4. Varied Reaction Times

Some market events trigger instant reactions; others unfold slowly over days, weeks, or even months. Thorp found edge in both. For example, statistical arbitrage plays may exploit slow corrections, while options mispricing may hinge on immediate reactions. The ability to judge the reaction window is a competitive advantage in itself.

How to Exploit Market Inefficiencies

Having identified the cracks in the system, Thorp laid out a framework for how to exploit them. These principles remain just as relevant today:

• Early Access to High-Quality Information

Speed matters — but so does signal quality. Thorp stressed the value of acquiring actionable insights early, while filtering out noise. In the age of AI and information overload, curation and timing are more important than ever.

• Disciplined Rationality

No matter how compelling a trade setup may look, it must survive cold-blooded analysis. Thorp believed that an edge only exists if the case for it holds up under logical scrutiny and statistical testing. Emotion and FOMO have no place in execution.

• Superior Analytical Techniques

From convertible arbitrage to options pricing and blackjack systems, Thorp was relentless in developing models others hadn’t seen yet. He proved that edge often lies in new ways of seeing familiar data — a mindset modern quants now emulate.

• Timing Is Everything

Even a good trade idea can fail if it’s entered too late. Thorp understood that mispricings don’t last forever — and the earliest entrants tend to reap the most upside. His strategies were not just about “what” and “why,” but also “when.”

The Takeaway: Define Your Edge or Don’t Trade

Thorp’s legacy teaches us that successful trading isn’t about predicting the future — it’s about finding repeatable advantage in the present. Whether you’re using statistical arbitrage, technical patterns, or macro fundamentals, the rules remain:

- Find inefficiency

- Validate your edge

- Size responsibly

- Adapt relentlessly

In essence, Ed Thorp’s wisdom underscores the importance of cultivating a competitive edge in trading. It’s not merely about entering the market; it’s about entering with a well-defined advantage, making informed decisions, and having the discipline to seize opportunities when they arise. As Warren Buffett aptly puts it, “Only swing at the fat pitches.”